RISK REDUCTION

Defensible Space

Home Hardening

Structural Ignitability

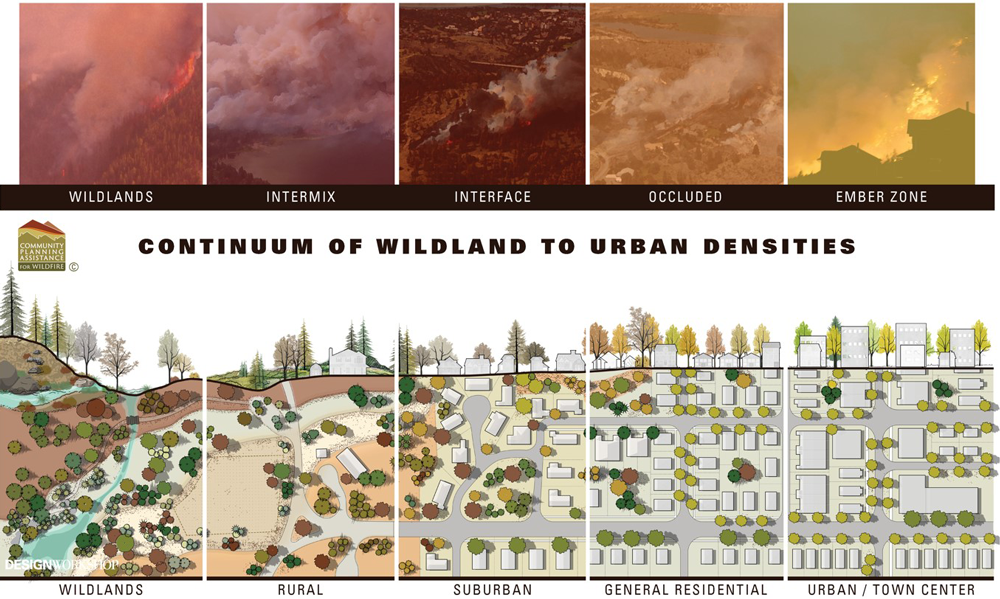

In the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) where natural fuels and structure fuels are intermixed, fire behavior is complex and difficult to predict. Research based on modeling, observations, and case studies in the WUI indicates that structure ignitability during wildland fires depends largely on the characteristics and building materials of the home and its immediate surroundings.

The dispersion of burning embers from wildfires is the most likely cause of home ignitions. When embers land near or on a structure, they can ignite nearby vegetation or accumulated debris on the roof or in the gutter. Embers can also enter the structure through openings such as an open window or vent, and could ignite the interior of the structure or debris in the attic. Wildfire can further ignite structures through direct flame contact and/or radiant heat. For this reason, it is important that structures and property in the WUI are less prone to ignition by ember dispersion, direct flame contact, and radiant heat.

The California Building Code (CBC)—Chapter 7A specifically—addresses the wildland fire threat to structures by requiring that structures located in state or locally designated WUI areas be built of fire-resistant materials. There are also requirements for fire safe construction in Chapter 13 Sonoma County Fire Code. Currently, the code specifies fire safe requirements that only apply to new construction or extensive remodels.

Building in the Grove street corridor tends to be unique projects on a single lot, either new construction or extensive remodels, with different design and construction teams. Studies show that more recently constructed buildings are more likely to survive a wild fire due to fire resistant materials required by building codes.

The best opportunity to protect our largely built out community would be to harden existing properties. Large ticket items such as roofing and windows require periodic replacement albeit at long periods of up to 40 years. Sonoma County requires Class A Roofing Materials for replacement of more than 50% of an existing roof or a remodel adding 640 square feet or more of floor area. Class A is the highest rating, offering the highest resistance to fire, and unrated is the worst. Examples of a Class A roof covering include concrete or clay roof tiles, fiberglass asphalt composition shingles and metal roofs. Since most roofing projects require permits, this code requirement will lead to hardening of vulnerable roof surfaces over time. However, there are educational opportunities to evaluate existing roof stocks for fire resistance and to encourage upgrades sooner rather than later as appropriate.

On the other hand, Sonoma County does not require permits to replace existing windows provided the replacement windows are the same size as existing windows. Windows form a front-line defense in fire hardening, and selecting double or triple pane, tempered or annealed glass, provide significantly greater fire resistance than do the single pane glass windows that exist in some older homes. In addition, metal window screens and some window films enhance fire resistance. Finally, shutting windows in a wild fire scenario is crucial to prevent embers from entering a home and igniting a fire. Windows present an excellent opportunity to educate building owners. New windows also reduce energy use and ambient sound penetration into the home.

Some of the most effective things that can be done to fire harden a structure do not require large expenditures. In a study based on more than forty thousand records of structures exposed to wildfires from 2013 to 2018, it was found that, overall, defensible space distance explained very little variation in home survival and that structural characteristics were generally more important. Structure survival was highest when homes had enclosed or no eaves, screened vents, and multiple-pane windows previously discussed. These results suggest that one of the potentially most effective methods of protecting homes from wildfire destruction would be to perform simple building retrofits, such as placing fine mesh screens over vents and coverings other openings in the structures, such as gaps in roofs, and enclosing structure eaves.

Similarly, since firebrands or embers are the most common source of structure ignition, it is important to ensure that all building material joints and connections are well maintained and sealed or caulked as necessary. Lap joints in siding, blocking in eaves and window frames are all areas that can separate creating gaps allowing wind driven embers to enter and ignite the structure. Other maintenance items such as cleaning leaves from down gutters, removing accumulated leaves, debris, and combustible materials from under decks or wind trap areas are important to remaining fire safe. Combustible materials, such as fire wood, stored adjacent to structures or on decks should be relocated.

Some types of roofing, such as barrel tiles, can have openings that may collect debris and trap embers allowing embers to ignite roofs. Bird stops, or other types of sealing can remediate this hazard.

All of these items are relatively low cost and would significantly reduce structural ignitability. This can be addressed programmatically in two ways. First, we can educate people through public events, such as fire fairs. There are three HOA or Neighborhood Associations in our district, we can request to present at their events.

Finally, inspection of structures at the request of owners to identify opportunities to fire harden can be performed by trained inspectors. The Wildland Fire Assessment Program (WFAP) is a joint effort by the U.S. Forest Service and the NVFC to provide volunteer firefighters and non-operational personnel, such as Fire Corps members, with training on how to properly conduct assessments for homes located in the wildland-urban interface (WUI). This is the first program targeted to volunteers that specifically prepares them to evaluate a home and provide residents with recommendations to protect their property from wildfires in order to make their community more fire adapted. WFAP offers in person and online training, and a tool kit for conducting assessments. The GFSC will recruit, train and offer assessments to property owners in our area.

In the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) where natural fuels and structure fuels are intermixed, fire behavior is complex and difficult to predict. Research based on modeling, observations, and case studies in the WUI indicates that structure ignitability during wildland fires depends largely on the characteristics and building materials of the home and its immediate surroundings.

The dispersion of burning embers from wildfires is the most likely cause of home ignitions. When embers land near or on a structure, they can ignite nearby vegetation or accumulated debris on the roof or in the gutter. Embers can also enter the structure through openings such as an open window or vent, and could ignite the interior of the structure or debris in the attic. Wildfire can further ignite structures through direct flame contact and/or radiant heat. For this reason, it is important that structures and property in the WUI are less prone to ignition by ember dispersion, direct flame contact, and radiant heat.

The California Building Code (CBC)—Chapter 7A specifically—addresses the wildland fire threat to structures by requiring that structures located in state or locally designated WUI areas be built of fire-resistant materials. There are also requirements for fire safe construction in Chapter 13 Sonoma County Fire Code. Currently, the code specifies fire safe requirements that only apply to new construction or extensive remodels.

Building in the Grove street corridor tends to be unique projects on a single lot, either new construction or extensive remodels, with different design and construction teams. Studies show that more recently constructed buildings are more likely to survive a wild fire due to fire resistant materials required by building codes.

The best opportunity to protect our largely built out community would be to harden existing properties. Large ticket items such as roofing and windows require periodic replacement albeit at long periods of up to 40 years. Sonoma County requires Class A Roofing Materials for replacement of more than 50% of an existing roof or a remodel adding 640 square feet or more of floor area. Class A is the highest rating, offering the highest resistance to fire, and unrated is the worst. Examples of a Class A roof covering include concrete or clay roof tiles, fiberglass asphalt composition shingles and metal roofs. Since most roofing projects require permits, this code requirement will lead to hardening of vulnerable roof surfaces over time. However, there are educational opportunities to evaluate existing roof stocks for fire resistance and to encourage upgrades sooner rather than later as appropriate.

On the other hand, Sonoma County does not require permits to replace existing windows provided the replacement windows are the same size as existing windows. Windows form a front-line defense in fire hardening, and selecting double or triple pane, tempered or annealed glass, provide significantly greater fire resistance than do the single pane glass windows that exist in some older homes. In addition, metal window screens and some window films enhance fire resistance. Finally, shutting windows in a wild fire scenario is crucial to prevent embers from entering a home and igniting a fire. Windows present an excellent opportunity to educate building owners. New windows also reduce energy use and ambient sound penetration into the home.

Some of the most effective things that can be done to fire harden a structure do not require large expenditures. In a study based on more than forty thousand records of structures exposed to wildfires from 2013 to 2018, it was found that, overall, defensible space distance explained very little variation in home survival and that structural characteristics were generally more important. Structure survival was highest when homes had enclosed or no eaves, screened vents, and multiple-pane windows previously discussed. These results suggest that one of the potentially most effective methods of protecting homes from wildfire destruction would be to perform simple building retrofits, such as placing fine mesh screens over vents and coverings other openings in the structures, such as gaps in roofs, and enclosing structure eaves.

Similarly, since firebrands or embers are the most common source of structure ignition, it is important to ensure that all building material joints and connections are well maintained and sealed or caulked as necessary. Lap joints in siding, blocking in eaves and window frames are all areas that can separate creating gaps allowing wind driven embers to enter and ignite the structure. Other maintenance items such as cleaning leaves from down gutters, removing accumulated leaves, debris, and combustible materials from under decks or wind trap areas are important to remaining fire safe. Combustible materials, such as fire wood, stored adjacent to structures or on decks should be relocated.

Some types of roofing, such as barrel tiles, can have openings that may collect debris and trap embers allowing embers to ignite roofs. Bird stops, or other types of sealing can remediate this hazard.

All of these items are relatively low cost and would significantly reduce structural ignitability. This can be addressed programmatically in two ways. First, we can educate people through public events, such as fire fairs. There are three HOA or Neighborhood Associations in our district, we can request to present at their events.

Finally, inspection of structures at the request of owners to identify opportunities to fire harden can be performed by trained inspectors. The Wildland Fire Assessment Program (WFAP) is a joint effort by the U.S. Forest Service and the NVFC to provide volunteer firefighters and non-operational personnel, such as Fire Corps members, with training on how to properly conduct assessments for homes located in the wildland-urban interface (WUI). This is the first program targeted to volunteers that specifically prepares them to evaluate a home and provide residents with recommendations to protect their property from wildfires in order to make their community more fire adapted. WFAP offers in person and online training, and a tool kit for conducting assessments. The GFSC will recruit, train and offer assessments to property owners in our area.

Fuel Mitigation

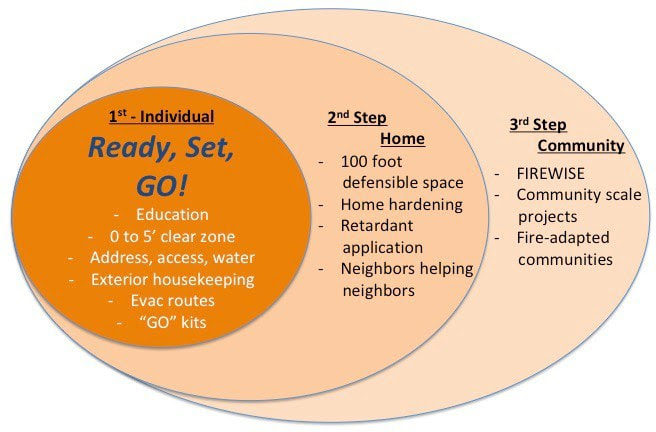

1st Step – Individual Action

Individual actions are those that a single person can accomplish wearing a mask and not violating “social distancing” practices of six feet separation between individuals. Start with the basic individual preparation steps in the Ready, Set, GO! program and the best practices for COVID-19 safety below. “Ready” is a two-part action: education and taking personal action steps. Become aware of the educational materials provided by your local fire department, Fire Safe Council, FAC, FIREWISE and insurance companies. The goal here is to increase your understanding / situational awareness of your wildland fire problem and fire behavior in your geographical area. You should then learn how to take basic steps to prepare your home and understand evacuation routes/terms and procedures.

While practicing “social distancing,” go outside of your home and remove combustible vegetation, greenwaste/mulch, or bark within the first 5-feet surrounding your home. Then relocate firewood storage away from the house and remove combustible furniture and other flammable materials. Clean out your gutters and remove the leaf litter on your roof. Ensure that a fire engine can see your address and that they have a 14’ x 14’ clearance from trees and shrubs. Finally, make sure that you have your pool, water tank, hydrant and garden hoses ready, if needed.

“Set” is being ready to evacuate (have your “GO” kit ready) monitoring the weather and “Red Flag” conditions, always being on alert. “GO!” means to act early to self-evacuate or obey law enforcement’s evacuation direction.

The goal is to eliminate the immediate flying ember hazards and to escape safely.

2nd Step - Homes

Depending upon your situation and capabilities, perform or hire someone to create a 100-foot defensible space zone. Ask your contractor to adhere to the recommended COVID-19 safety rules. Begin to take positive actions to harden your home by simply changing attic/sub-floor vent screening size to 1/8” (eave and cornice vents should be baffled).

More elaborate hardening actions can be taken based upon your specific situation. In lieu of doing extensive landscape projects and modifying wood decks, consider applying a fire retardant spray. Most of these products will last for a fire season even with minimal rainfall.

As we finish focusing on our individual home, extend offers to help neighbors, especially those who cannot help themselves. You can begin to build community resilience by expending your mitigation efforts to others, similar to building a chain or barrier.

3rd Step - Community

The third step involves more community scale projects. Typical examples are shaded fuel breaks, improving access roads and conducting fuel treatments. The overall goal is to truly build a fire-adapted community that can withstand a wildfire even if there are no fire resources available.

Individual actions are those that a single person can accomplish wearing a mask and not violating “social distancing” practices of six feet separation between individuals. Start with the basic individual preparation steps in the Ready, Set, GO! program and the best practices for COVID-19 safety below. “Ready” is a two-part action: education and taking personal action steps. Become aware of the educational materials provided by your local fire department, Fire Safe Council, FAC, FIREWISE and insurance companies. The goal here is to increase your understanding / situational awareness of your wildland fire problem and fire behavior in your geographical area. You should then learn how to take basic steps to prepare your home and understand evacuation routes/terms and procedures.

While practicing “social distancing,” go outside of your home and remove combustible vegetation, greenwaste/mulch, or bark within the first 5-feet surrounding your home. Then relocate firewood storage away from the house and remove combustible furniture and other flammable materials. Clean out your gutters and remove the leaf litter on your roof. Ensure that a fire engine can see your address and that they have a 14’ x 14’ clearance from trees and shrubs. Finally, make sure that you have your pool, water tank, hydrant and garden hoses ready, if needed.

“Set” is being ready to evacuate (have your “GO” kit ready) monitoring the weather and “Red Flag” conditions, always being on alert. “GO!” means to act early to self-evacuate or obey law enforcement’s evacuation direction.

The goal is to eliminate the immediate flying ember hazards and to escape safely.

2nd Step - Homes

Depending upon your situation and capabilities, perform or hire someone to create a 100-foot defensible space zone. Ask your contractor to adhere to the recommended COVID-19 safety rules. Begin to take positive actions to harden your home by simply changing attic/sub-floor vent screening size to 1/8” (eave and cornice vents should be baffled).

More elaborate hardening actions can be taken based upon your specific situation. In lieu of doing extensive landscape projects and modifying wood decks, consider applying a fire retardant spray. Most of these products will last for a fire season even with minimal rainfall.

As we finish focusing on our individual home, extend offers to help neighbors, especially those who cannot help themselves. You can begin to build community resilience by expending your mitigation efforts to others, similar to building a chain or barrier.

3rd Step - Community

The third step involves more community scale projects. Typical examples are shaded fuel breaks, improving access roads and conducting fuel treatments. The overall goal is to truly build a fire-adapted community that can withstand a wildfire even if there are no fire resources available.